Unsubstantiated fictional tale #1:

“The book is based on the author’s personal experience in the 60s.”

Fact:

Kathryn Stockett was born in 1969. Therefore, she has no “personal experience” regarding the 1960s. What is true is that Stockett was cared for and had mutual affection for a maid named Demetrie, until Demetrie’s death in the mid 1980s when Stockett was about sixteen. Stockett admits this in the acknowledgments section “”Too Little, Too Late” and several interviews.

And Stockett has admitted real life events that were mentioned to her by others made their way into the novel. Not only real life events, but the author also used observations of individuals close to her, those who may or may not have given their permission to do so:

This information is from the Atlanta Journal Constitution (items in bold are my doing):

”In past interviews with the AJC, Stockett has said she wrote “The Help” as part of a writing club. She used names of people she knew simply because they were handy, she said.

“When I was writing this book, I never thought anyone else would read it, so I didn’t get real creative with the names,” Stockett told us in 2009. “I just used people I knew. Some of them aren’t talking to me right now, but I feel like they’ll come around.”

She has repeatedly called the book, which has been adapted into a film, a work of fiction.

“I wrote it purely for me and finally had the guts to show it to my mother and my writing group, ” Stockett told us in the 2009 interview. “I was terrified when I realized it was going to be published.”

Link: http://blogs.ajc.com/the-buzz/2011/02/18/kathryn-stockett-author-of-the-help-sued/

Interview by the Publisher – Penguin Group

Excerpt:

Minny was the easiest to write because she’s based on my friend Octavia. I didn’t know Octavia very well at the time I was writing, but I’d watched her mannerisms and listened to her stories at parties. She’s an actress inLos Angeles, and you can just imagine the look on her face when some skinny white girl came up and said to her, “I’ve written a book and you’re one of the main characters.” She kind of chuckled and said, “Well, good for you.”

http://us.penguingroup.com/static/rguides/us/help.html

Back in 2009, here’s the greeting Stockett gave on the Barnes and Noble site:

“. . . I usually have my mind on a story– either mine or someone else’s– where the tomatoes are riper, the itches are itchier, the sun burns hotter than in regular life. ”

“Grandaddy told me the story of Cat-bite, who is in the book. He was driving along and saw a young black girl being attacked by a cat- just a regular old house feline- that had rabies and wouldn’t turn this poor little girl loose. Grandaddy saved her and took her to the hospital for the rabies shots- in the stomach, for 21 days. It was many years later that she tracked Grandaddy down and thanked him again, for what he’d done.

Grandaddy also gave me a great sense of what people felt and thought during the early 1960′s. There was a feeling thatMississippiwas the world. You were more interested in the local farm report than what the President was doing inWashington. The most important events to you were happening right there in your neighborhood. I like that idea and tried to employ that state of mind in The Help.”

So far Stockett has admitted to using the real life events or actual people as inspiration for her character creations:

Stockett’s grandfather, the maid Demetrie and the actress Octavia Spencer are three that have been publicly identified. There’s also the matter of the lawsuit against the author by a maid named Ablene Cooper, who believes the character of Aibileen was based on her, and not Demetrie. Ablene Cooper has a gold tooth and a deceased son, much like Aibileen Clark in the novel. But Stockett still insists that Aibileen was based on Demetrie.

While Stockett has been open about basing Aibileen on Demetrie, the author hasn’t commented on whether Leroy is based on Demetrie’s abusive husband Clyde/Plunk. But Aibileen’s “no-account” husband is named Clyde. And Leroy, Minny’s husband is frequently drunk and abusive.

Take a look at how Stockett decribes Clyde/Plunk and decide for yourself:

Demetrie was stout and dark-skinned and, by then, married to a mean, abusive drinker named Clyde. She wouldn’t answer me when I asked questions about him. But besides the subject of Clyde, she’d talk to us all day. (Too little, too late Pg 447)

Now recall the page where Skeeter asks Minny about Leroy, and Minny refuses to discuss her husband, telling Skeeter to back off.

What’s also interesting is how Stockett omitted information on the Citizen’s Council of Jackson, formerly known as the White Citizen’s Council of Jackson and one of the main opponents of integration. But doing that may have forced to author to look where she didn’t want to go, and that was to face how segregation was neither “funny” or “entertaining” for those subjected to it.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #2:

“The audio version is so much better, all the characters speak with a southern accent, so there’s really no need to complain.”

There’s plenty to be offended and insulted by in The Help. Because a major problem with the book isn’t just how the black characters speak, but what they say, and far too many scenes in the novel simply validate the bigotry of the times. That Stockett chose to have the black characters voice their displeasure with black males and one has a major issue with her own skin color, as well as royally dissing their loved ones and their community doesn’t make the offense any less.

And here’s the kicker, somehow Stockett believes she’s created “admirable” characters. I. Don’t. Think. So.

No white female in the novel makes this fairly all encompassing statement about white males:

Plenty of black men leave their families behind like trash in a dump, but it’s not something the colored woman do. We’ve got kids to think about – Minny Jackson (Pg 311)

Frankly, I think Stockett and her publisher owe the black community an apology for that intrusive omnipresent narrator (Stockett herself) swooping in to make sociological assessments on what she perceives is wrong with the black community. It’s especially telling when comparing what the black characters say versus the white characters, where there’s a marked difference and it’s not just a dialect or class difference.

None of the white characters compare their skin color to any insect, yet Stockett has Aibileen doing a highly degrading color swatch test with a roach to decide who’s the blackest. The roach wins by the way.

And I couldn’t find the section in the novel where the white characters talk about their vagina’s as “cootchies” or any other pet name as Stockett has Aibileen and Minny doing. No, there’s no “cootchie spoilt as a rotten oyster” for these delicate southern belles. As the novel continues, it’s also clear Stockett has fallen into the trap of thinking that somehow slipping into the frame of mind of a black woman means you can act a fool and everyone just loves it. Living vicariously through her black characters, Stockett actually admitted this in an interview:

Oprah Radio host Nate Berkus (no transcript available)

Excerpt:

“Yes absolutely. And you learned, I think as an African American in Mississippi to be very careful with your words and then one of my favorite scenes from the book is when all the maids were on the bus and they get to talk about all their white employers and they get to make fun of them as openly as they can.”

http://www.oprah.com/oprahradio/Author-Kathryn-Stockett-Audio

Now, just why would a black bus rider in still segregated Mississippi be stupid enough to act up on a bus where they still had to sit in the back (had Stockett done her research, she would have realized that). All Jackson bus drivers were still white, and Freedom Riders were pouring into the city not only to work for voting rights, but to integrate bus terminals, buses and public eating establishments. Jackson, Mississippi in the early 60s still behaved as if the Federal Law against segregation on interstate travel still existed.

Stockett’s quote refers to the scene where the reader is introduced to the “sassy” maid Minny:

I spot Minny in the back seat. Minny short and big, got shiny black curls. She setting with her legs splayed, her thick arms crossed. She seventeen years younger than I am. Minny could probably lift this bus up over her head if she wanted to. Old lady like me’s lucky to have her as a friend.

I take the seat in front of her, turn around and listen. Everbody like to listen to Minny.

” . . . so I said, Miss Walters, the world don’t want to see your naked white behind any more than they want to see my black one. Now, get in this house and put your underpants and some clothes on.”

“On the front porch? Naked?” Kiki Brown ask.

“Her behind hanging to her knees.”

The bus is laughing and chuckling and shaking they heads.

“Law, that woman crazy,” Kiki say. “I don’t know how you always seem to get the crazy ones, Minny.”

“Oh, like your Miss Paterson ain’t?” Minny say to Kiki. “Shoot, she call the roll a the crazy club.” The whole bus be laughing now cause Minny don’t like nobody talking bad about her white lady except herself. That’s her job and she own the rights. (Aibileen describing Minny, Pg 13)

Sigh . . . what I got from this scene is a big woman with her legs wide open on a public bus, loud talking. Only considering the times, Minny would have been either arrested, put off the bus or worse. Taken away for a beat down by police.

A bit further on, Stockett feels so comfortable pretending to be a black female, she concocts an imaginary conversation where Aibileen and Minny talk about cootchies, or one cootchie in particular. Minny mentions that the woman Aibileen’s estranged spouse Clyde has run off with named Cocoa, contracted a venereal disease a week after their departure (apparently from Clyde).

Just as some bigoted whites used the slur of blacks having “diseases” and being “immoral” as an excuse to block integation and equality, Stockett creates the character of Cocoa, and has the obsurd Cocoa, Cootchie, Clyde “spoilt cootchie” scene on pages 23 and 24, where Aibilene doesn’t realize she too might have contracted a venereal disease, and that most Christians devoted to God would be highly offended if someone thought they’re somehow gained the power through prayer to call down a plague on another individual. Besides that, Stockett has Aibileen invoking one of the stupidest lines in the novel “You saying people think I got the black magic?”

Thereby cementing the author’s misguided attempt to provide humor by showing that she too believes blacks and voodoo or “black magic” must go hand in hand. So when Stockett talks about putting “different” voices on the page, she’s not just refering to having the white characters speak as if they’re from the North and the black characters still on a plantation from the Civil War. Because from the whole “spoilt cootchie” to “no-account” males, to women with skin the color of “asphalt” or “black as night”, or so black Skeeter “can’t tell them apart”, Stockett makes it quite clear that African Americans are quite different in her eyes than whites, in every way possible.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #3:

“Have you read the book? Read the book, you’ll love it”

I mean, WTF? Listen, when someone comes on a message board and expresses their dislike for the novel, I have no idea why some posters who have read the book assume some people AKA black readers haven’t. What’s even whackier, is when some of these same readers who love the novel are challenged, they then use the excuse “Oh, I don’t know about that part.” or “I don’t remember that part so I can’t comment on it” or some other weak excuse like “It was the message in the book that’s the point.”

And what message would that be?

That black women who talk trash about their own culture make the best Mammies, expecially if they abstain from sex and are ready at the drop of a hat to grovel? Or that now’s the perfect time to reminisce about the good ol’ days when blacks were forced to do what they were told. Or how about in a mere two years, a woman can get over the shock of losing her only child (Aibileen). There are countless movies where the plot revolves around how hard it is to get over the death of a child, yet Skeeter mourns over Constantine more than Aibileen does for her son. There are no scenes where Aibileen cries tears over Treelore, but she sure does turn on the waterworks in happiness over Skeeter at the book’s end. If Stockett had ever lost a child, she’d know that this premise of stunted grief and the ability to just grab another child (Mae Mobley) to smother love on is absurd and highly insensitive, especially since Aibileen doesn’t initiate any affection towards Minny’s children. And it’s just another way the book makes it appear as though how African Americans feel or deal with life is totally the opposite of how whites do. We grieve. We cry. We mourn for years, and there is no tidy “closure”. We create foundations and charities in our child’s name, just like everyone else, because we’re HUMAN.

Or how about this message, that anyone who dares to offer an opposing viewpoint on this novel is “uppity” or has “attitude”. Well hell, I’ll be your Huckleberry.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #4:

“Skeeter’s not the “white savior” of the novel. The maids are admirable and do contribute to their novel”

I beg to differ. Skeeter was indeed set up by the author to be the “savior” but I have no problem agreeing to disagree on this.

In theory, having a young white woman lead a fictional rights revolution by recording the stories of several black maids is so heartwarming, it should have worked.

Until you realize that Skeeter never reveals whether she believes blacks and whites are equal, or even that segregation is wrong.

Skeeter appears to be an eager opportunist as well as a bit detached from what was happening in her own city. And this is after the woman graduated from Ole Miss with a degree in journalism. Yet here’s what she says about national, breaking news on James Meredith:

The picture pans back and forth and there is my old administration building. Governor Ross Barnett stands with his arms crossed, looking at the tall Negro (James Meredith) in the eye. Next to the governor is our Senator Whitworth, whose son Hilly’s been trying to set me up with on a blind date.

I watch the television, riveted. Yet I am neither thrilled nor disappointed by the news they might let a colored man into Ole Miss, just surprised. (Skeeter, Pg 83)

The nation was on edge regarding the events in Mississippi. In the end, Two people died (including a French reporter) and whites rioted on campus, causing President Kennedy to send in the National Guard (they were already there protecting James Meredith). Yet does Skeeter note this, or rather Stockett include the riot and its aftermath in the book? Nope. Just like there’s no mention of SNCC, CORE or information on other civil rights organizations, or college aged students from all over the country flooding into Jackson. See, Skeeter didn’t have to go it alone. But perhaps these other events transpiring in Jackson and agencies fighting for true equality would have detracted from holding Skeeter up as a rogue “savior”, even though Skeeter sneaks about in the dark of night and never really puts herself in danger. Oh, it’s implied in the novel, but Stockett admits in her video interview with Katie Couric of CBS that she’d never let any harm come to her “characters”.

Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjIowZrH4iM

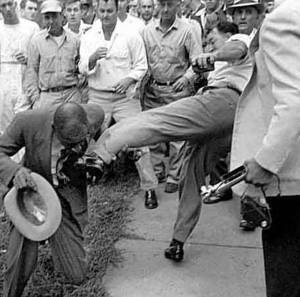

But when real rights activists, like nineteen year old Joan Trumpaer Mulholland enroll in all black Tougaloo college (the same one Yule May Crookle wanted to send her twins to) and takes part in staging a sit in at Woolworths, or winds up getting a cavity search (including insertion of her vagina) while imprisoned, Skeeter’s antics come up woefully short.

Here’s another excerpt on Skeeter’s de-sensitized nature. The sentence in bold is my doing:

I search through card catalogues and scan the shelves, but find nothing about domestic workers. In nonfiction, I spot a single copy of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. I grab it, excited to deliver it to Aibileen, but when I open it, I see the middle seciton has been ripped out. Inside, someone has written NIGGER BOOK in purple crayon. I am not as disturbed by the words as by the fact that the handwriting looks like a third grader’s. I glance arond, push the book in my satchel. It seems better than putting it back on the shelf. (Pg 172)

What Skeeter’s good at though, is delegating work and getting information that she needs out of the black help, especially Saint Aibileen.

No, Skeeter doesn’t do much of anything except type and bitch and moan about her mother, Constantine, and what’s taking Aibileen so long to get all the maids together. But I guess that’s okay, since the book is really about Skeeter, and not the maids.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #5:

The lynching of Carl Roberts

I still haven’t found concrete information that this person even existed.

There’s no Carl Roberts in any recorded archive of those lynched in Mississippi. And I haven’t found a Life magazine article similar to the one mentioned by Carlton Phelan and Senator Stoolie Whitworth on page 267:

The Senator leans back in his chair. “Did you see that piece they did in Life magazine? One before Medgar Evers, about what’s is- name- Carl Roberts?”

I look up, surprised to find the Senator is aiming his question at me. I blink, confused, hoping it’s because of my job at the newspaper. “It was . . .he was lynched. For saying the governor was . . .” I stop, not because I’ve forgotten the words. but because I remember them.

“Pathetic,” The Senator says, now turning to my father. “With the morals of a streetwalker.”

I exhale, relieved the attention is off me. I look at Stuart to gauge his reaction to this. I’ve never asked him his position on civil rights. But I don’t think he’s even listening to the conversation. The anger around his mouth has turned flat and cold. (Skeeter, Pg 267)

I’m not saying it never happened though. I just haven’t found information that would lend credence to this section of the novel. I do notice when individuals come on this site, many wind up here searching for info on the Carl Roberts story in the book.

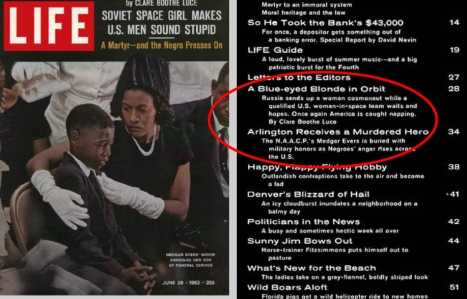

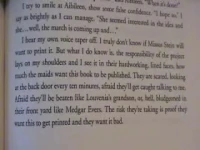

Life Magazine, June 1963. Note the items circled in red. You can find more old Life magazines at this site: http://www.oldlife.net

Link: http://www.oldlife.net/index.php

On page 239 of the hard cover text, Skeeter says:

In a rare breeze, my copy of Life magazine flutters. Audrey Hepburn smiles on the cover, no sweat beading on her upper lip. I pick it up and finger the wrinkled pages, flip to the story on the Soviet Space Girl. I already know what’s on the next page. Behind her face is a picture of Carl Roberts, a colored schoolteacher from Pelahatchie, forty miles from here. “In April, Carl Roberts told Washington reporters what it means to be a black man in Mississippi, calling the governor ‘a pathetic man with the morals of a streetwalker.’ Roberts was found cattle-branded and hung from a pecan tree.”

They’d killed Carl Roberts for speaking out, for talking. I think about how it would be, three months ago, to get a dozen maids to talk to me. Like they’d just been waiting all this time, to spill their stories to a white woman. How stupid I’d been.” (Pg 239, Skeeter)

In the screen grab above, please note what I’ve circled in red. There’s an article in the real Life magazine about the blonde Soviet woman in space. The next article covers Medgar Evers funeral. If Carl Roberts is fictional, I don’t know why Stockett’s editors would have her make up a character when Evers real death was right there in the same magazine.

So far there’s nothing on Carl Roberts, but something may turn up. Perhaps the name was changed, or the definition shouldn’t be “lynching” regarding the supposed death. If someone has more information, please share by leaving a comment.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #6:

It’s important to note that Stockett has gone on record stating the real life maid of her grandparents inspired not just Aibileen, but most of the maids in the novel. Below is an actual photo of Demterie. Now, read what the author says about her:

“Demetrie was stout and dark-skinned and, by then married to a mean, abusive drinker named Clyde. She wouldn’t answer me when I asked about him. But besides the subject of Clyde, she’s talk to us all day.” Kathryn Stockett in her own words, Too Little Too Late, Pg 447 of the novel

Demetrie was not a dark skinned woman. At least not the way Stockett described most of the maids in the novel. Because the often repeated word she uses is “Black”, as in “Black like asphalt”, “Black as night”, “blacker by ten shades”.

That night after supper, me and that cockroach stare each other down across the kitchen floor. He big, inch, inch an a half. He black. Blacker than me. Aibileen’s battle of wills with a cockroach (Pg 189)

While visiting Constantine, this character talks about playing with two little girls who were “so black I couldn’t tell them apart and called them both just Mary.” (Pg 62) – Skeeter

I clear my throat, produce a nervous smile. Minny doesn’t smile back. She is fat and short and strong. Her skin is blacker than Aibileen’s by ten shades, and shiny and taut, like a pair of new patent shoes. – Skeeter’s first impression of Minny (Pg 164)

The women are tall, short, black like asphalt or caramel brown. If your skin is too white, I’m told, you’ll never get hired The blacker the better. – (Pg 257) Skeeter

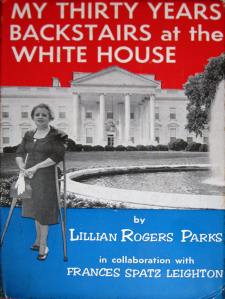

Demetrie wasn’t the only non “Black as night” African American hired as a domestic. One of the most famous is Lillian Rodgers Parks, who wrote of her experience as a seamstress and a maid in her many years of service ( 1929-1960) at the White House:

Lillian’s story was a popular made for TV miniseries during the late 70s. The series is out on DVD and its worth purchasing. More about Backstairs at the White House, starring Leslie Uggams, Olivia Cole, Leslie Nielson, Paul Winfield, Robert Hooks, Cloris Leachman, Robert Vaughn, Lou Gossett Jr., and a host of other stars both black and white can be found here.

Stockett’s grandparents maid Demetrie had more than a “friendly softness” in the middle. While I lack a photo of Ablene Cooper, the woman who filed suit (reportedly with the help of Stockett’s brother) against Kathryn Stockett, it’s already been verified that Cooper has an adult deceased son, a gold tooth, and if she’s darker than Demetrie her allegation that Stockett mis-appropriated her likeness might have some merit.

**Update**

Here’s a picture of Abilene Cooper. And no matter how much Stockett protests, here’s where the author got her description of Aibileen Clark:

One thing for certain, here’s what was manufactured and popular during segregation to represent black domestics. Compare the skin color and girth to Stockett’s descriptions and these may possibly be where the author got her “inspiration” on skin tone and image.

Mammy lamp. Not sold on HSN, but popular during segregation. Image from Ferris State Museum of Jim Crow Memorabilia

And so, without anyone checking to see if what Stockett claimed was true, we have the scene in the movie where all the “blacker the better” maids are in the same room. Which poses another problem. Because in the novel Stockett segregated the characters with more white characteristics like Lulabelle, Yule May and Gretchen. All three of them speak like the white characters in the book, two are described as “trim” (Gretchen and Yule May) and all possess a fiery belligerence that Aibileen, Minny and Constantine, Stockett’s Mammy-fied trio sorely needed. The picture below is fiction of the worst kind.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #7:

“Black people are just mad because a white woman wrote this novel.”

This retort appears to be a popular one whenever love isn’t expressed for Kathyrn Stockett’s book.

Yes, what other reason could it be that an African American could have a negative opinion besides the racially hot excuse that “a white woman wrote this book ” thus that’s why some object to it.

For the record, most published novels are by WHITE men and women in America. That’s nothing new. And African Americans are quite used to laying down dollars even when a minority isn’t part of the cast.

Kathryn Stockett wrote a book that turned out to be a bestseller. But so did Sarah Palin. That doesn’t mean either novel is a literary masterpiece and doesn’t have failings. Some loved both books, some didn’t. Some will love The Help, and others won’t.

Why an African American ends up not enamored with the book, and in some cases also the film is important not only to other African Americans, but it should also be to whites who may wonder why either one isn’t uniformly “beloved.”

Same can be said for other works created by whites portraying the black culture. The Jazz Singer, Birth of Nation and other movies had stereotypical scenes and dialogue with cork painted, black faced white actors.

Many Americans loved those films too, and didn’t think anything was wrong. African American critics and some sympathetic whites had to point out why the movies were offensive and not well received by the black community.

Next came real African Americans playing stereotypical roles, from Stepin Fetchit to Eat n’ Sleep to even Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel. They had to act and speak dialogue that was demeaning, yet audiences howled with laughter. Stepin Fetchit even became a millionaire for his antics.

The Help is simply a return to the past, with black actors playing the same roles Hollywood once strictly relegated African Americans to previously. And guess what? White writers wrote the scripts back then too. Seems everything old is new again.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #8:

“Whites were instrumental in helping black Americans gain equality. If it wasn’t for the intervention of white people, there would have been no civil rights movement.”

I actually got into a debate with a poster on another site who insisted that African Americans who didn’t enjoy The Help were just mad because of white contribution to the rights movement.

All I can say is this, yes there were casualities from both races in the fight for civil rights. But the freedom movement lasted for over one hundred years, not just in the 60s. During that time African Americans, overwhelmingly those male in sex were murdered because of their rights activities. And on this site, I do highlight individuals both black and white who gave their lives for equality. One unsung hero is William Moore.

Per Jerry Mitchell, a well known journalist who writes and documents the Civil Rights Movement:

“In the spring of 1963, William Moore of Baltimore, a white postal worker, decided to walk from Chattanooga, Tenn., to Jackson, Miss., to deliver a letter to Gov. Ross Barnett, urging him to break down the walls of segregation in Mississippi. . .

During his one-march man, Moore wore a sandwich board that read, “Equal Rights For All. Mississippi Or Bust.”

Along the way, he encountered plenty of hate. Some people threw rocks at him and yelled “n—– lover.”

On the night of April 28, 1963, while resting on his journey in Attalla, Ala., he was shot twice at close range. Kennedy called his killing ‘an ‘outrageous crime. ‘ ”

I’ll repeat again, African American males were the main target of those bigots who followed segregation to the letter. And they used many ways to inflame the animosity of others. Lies were spread about the black lifestyle, from blacks being immoral and carrying venereal diseases to the myth that black males only sought to rape white females, no matter what the age.

Advertisements contributed to portraying blacks both female and male as grinning, slow witted and grammar demolishing individuals who were born to serve whites, because we thought not to be “civilized” or as smart.

There were bogus studies used to justify the “difference” in the black and white race. We were considered better athletes and our physique bred for physical and menial jobs, but not qualified simply because of our skin color to be scientists, doctors, politicians, teachers, lawyers . . . in short, any profession that required the use of the mind over muscle.And in The Help, Kathryn Stockett unwittingly continues this propaganda.

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #9

“The Help isn’t a history book. It’s fiction.”

Agreed.

But using this excuse, and in this particular case, has become yet another means to give Stockett a pass for errors in the novel when another author would be called to task. Say for example an author wrote a book about 9/11 and claimed only one plane was involved. Since the tragedy of 9/11 is still so fresh, there would probably be an outcry on this inaccuracy, though the book is fiction.

The problem with The Help is that some of the history Stockett inserts in the novel is either plagued by errors elsewhere in the book or skewed in favor of the white characters.

By inserting real life events from the south during the 60s and framing characters around them, Stockett’s novel is fiction based on some actual facts. And those an author cannot change and dare not change. One glarring example is the death of Medgar Evers in the novel.

Sloppy research and editing left in the Medgar Evers error in the hard cover version of the book, which is especially embarrassing for an author playing up the fact that she’s from Jackson, Mississippi.

In a screenshot I’ve included of the book, Skeeter states “They are scared, looking at the back door every ten minutes, afraid they’ll get caught talking to me. Afraid they’ll be beaten like Louvenia’s grandson, or, hell, bludgeoned in their front yard like Medgar Evers.”

Medgar Evers was never “bludgeoned.” He was shot, and the book makes mention of his shooting in a moving scene with Aibileen and Minny facing the shock of his assassination. Evers was also a civil rights icon and has a statue erected in his honor in Mississippi. While its bad enough that the error was left in, when Stockett did her book tour in 2009, she repeated the line that “Evers was bludgeoned” in three known audio interviews, which brings up some troubling questions.

More info on the error left in the hard copy edition, Pg 277 can be found here:

https://acriticalreviewofthehelp.wordpress.com/2011/04/09/medgar-evers-error-in-the-help/

To my knowledge the error was quietly corrected in the ebook version. But how is it that the error wasn’t caught? Part of the reason comes from the director and screenwriter of the movie himself, Stockett’s good friend Tate Taylor. In an interview he admitted to about.com:

Tate Taylor: “We have a great relationship, Kathryn and I. It could have gone poorly, but when I outlined the movie from the book, we met in New York and I said, ‘This is what I’m going to do.’ There was only one thing she didn’t agree with and she was right.”

Can you say what it was?

Tate Taylor: “I didn’t think we should talk about the Jim Crow Laws because I felt like people know what that is and she told me when she wrote the novel, her editors in New York – highly educated people – had no clue about Jim Crow Laws. I go, ‘Are you kidding me?’ I know, I swear! You think people know. They don’t. So she goes, ‘I’m telling you put it in,’ and I did. I thought, being a Southerner, it was too much. ‘Oh really? Of course there’s Jim Crow Laws.’ That was the one thing.”

http://movies.about.com/od/thehelp/a/tate-taylor-interview.htm

More info on the how The Help got over, inspite of problems and mindset surrounding the book and the movie can be found here:

https://acriticalreviewofthehelp.wordpress.com/2011/07/16/the-help-got-over/

So the editors seem to have relied on Stockett’s info to be accurate. Only in the case of how Evers died, Stockett wasn’t. So how could the same author who wrote the prior scenes featuring Minny and Aibileen completely forget Evers had been shot when doing an interview? Because when Stockett speaks of Evers “bludgeoning” in those audio interviews, her speech is earnest, as if she really believes this is how he died.

No, The Help isn’t a history book. But the publisher’s PR played up the historic connotations in the novel. So while Stockett’s original manuscript may have been simply about Skeeter’s relationship with Constantine and Aibileen and the other maids, someone recognized the novel would be incomplete or called on the history it left out.

In a hasty attempt to add it, mistakes were made by the publisher and the author.

By Stockett setting her story in Jackson at the very moment the civil rights movement was at its peak, then making most of the maids and most of the white employers act as if they could come and go as they pleased without being affected, is simply revisionist fiction at its worst.

The boycotts by the local black community shut down white merchants, as well as freedom riders and reporters from liberal national magazines pouring into the city on the minds and the mouths of white citizens who called them “commies” and “trouble makers.” The police were out in force, so Stockett pretending that the very newspaper Skeeter worked for wouldn’t have sent out a reporter, or at the very least have a negative buzz in the newsroom is pure denial.

I’ve included scans from two popular newspapers during the time Stockett sets her novel in. The papers have now been revealed to be pro-segregationist in their views, however they at least give insight on how the real Jackson, Mississippi operated during segregation, as well as the cultural and social norms that prevailed.

More can be found here:

https://acriticalreviewofthehelp.wordpress.com/real-housewives-of-jackson/

Pretending the civil rights movement didn’t have as much of a foothold in Jackson and thus would hardly affect the daily comings and goings of not only the maids, but their employers was big error in my opinion (the height of offense comes from the character of Minny speaking ill of church member Shirley Boon’s effort to gather individuals to join in. Minny reads like a fool when she says “I told Shirley Boon her ass was too big to fit on a stool at Woolworth’s”) There’s also an inference that domestics, which included maids weren’t on the forefront of the freedom marches. By attempting to make Skeeter’s book concerning the maids tales either on par, or of greater importance than the very real civil rights movement (which would gain the maids lasting equality), Stockett turns Skeeter into the dreaded “white savior” trope.

The movie attempted to correct some of the errors in the novel, especially with Skeeter’s lack of interest in the racial upheaval of Jackson, which called into question her journalism degree from Ole Miss. As the former editor of her college newspaper, Skeeter would have been part of the crowd blocking James Meredith from entering her Alma Mater, or trying to get students to interview (which in turn would beef up her resume). But I understand why the novel veered from doing this.

Because it was only meant for light entertainment, and not to “stick” with readers. Thus Hilly is an over the top villainess, and appears to be the only resident in Jackson advocating a strict adherence to segregation.

In the novel Skeeter behaved as if she’d just graduated from high school and had no “nose for news” or inquisitive spark which would lead one to believe journalism was the correct major for her (Skeeter graduated with a degree in English and journalism).

Unsubstantiated fictional tale #10

“That’s how it really was back then.”

This goes hand in hand with #9. Whenever the book is called on historical accuracy, then the excuse is that the novel isn’t supposed to be a history lesson. Yet some of these same defenders will claim the book handles the time period faithfully. On the page that lists the book’s publishing information, The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is listed as:

1. Civil Rights movement – Fiction

2. African American women – Fiction

3. Jackson (Miss)- Fiction

This information comes from the publisher (if it doesn’t I hope someone leaves a comment as to who determines this aside from the publisher)

But with more information coming out regarding errors in the book that could easily have been googled, and the director/screenwriter proclaiming in an interview that the film was “historically accurate” I can see where there could be confusion.

“If you want to see a historically accurate portrayal of life in the sixties, but go behind the door and see the humanity and the love behind these courageous . . . – Tate Taylor, director and screenwriter of The Help

Link: http://www.pegasusnews.com/news/2011/aug/08/interview-director-star-the-help-why-see-movie/

I mentioned the Medgar Evers error in item #9. I’ll point out another error that could have easily been corrected with a simply internet search, since the records are online for the public to view.

Skeeter’s amnesia over James Meredith:

Skeeter claims to be “neither thrilled nor disappointed by the news that they might let a colored man into Ole Miss, just surprised.” Stockett has the character saying this as she sees James Meredith being blocked from entering Ole Miss on televsion, when records from the real Ole Miss indicate the school’s student newspaper wrote disparaging articles on Meredith in Feb of 1962. In the novel, Skeeter graduates in May of that same year. As the fictional editor of The Rebel Rouser, Skeeter would have known more than she let on, especially since her major was journalism. And more importantly, James Meredith attempted to legally enroll in the school in 1961. When Skeeter Phelan was a junior.

Scanned Document from The University of Mississippi Libraries: Digital Collections on line The Integration of the University of Mississippi

Link: http://clio.lib.olemiss.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/integration&CISOPTR=100&REC=20

So when some people make the claim that Stockett captures what really went on back then, it’s important to understand why it gets challenged.

And while it’s true that the novel and the movie attempt to show how badly blacks were treated, its how Stockett believes her African American maids dealt with these events that the author also got wrong. In the novel Aibileen is someone loathing of the skin she’s in. So much so, that she reads as if she lives vicariously through the white children she’s around. There’s even a scene where she drools over Yule May’s hair, stating “Yule May easy to recognize from the back cause she got such good hair, smooth, no nap to it.” (Pg 208).

Aibileen whines about her skin color, feeling the need to compare her complexion to a roach, (“He black, blacker than me”) and also Connor, Constantine’s absentee lover (“He was black as me”) in yet another stereotypical trope, that of the absentee black male who fathers a child only to leave.

With this type of inner dialogue Stockett appears to assume that blacks would rather be anyone but who we were born. And instead of her primary maid being heroic, Aibileen has a serious inferiority complex that makes her less than admirable. In addition, though the movie changes the reason why the maids decide to help Skeeter with the manuscript (Taylor uses Medgar Evers death as the catalyst instead of Hilly pressing charges against Yule May for stealing), look what Stockett has Aibileen thinking days after Evers murder:

“But after Mr. Evers got shot a week ago, lot a colored folks is frustrated in this town. Especially the younger ones, who ain’t built up a callus to it yet. . .” (Pg 207)

This reads more like Aibileen is resigned to it all. She’s speaking as if the youth in her congregation just need time to realize resistance is futile, as she has done. As written, Aibileen’s driving force is simply instilling love in her white charges, and that never changes even while she assists with the maids stories. Yet somehow she ignores Minny’s children, because there’s no scene where she coddles Minny’s youngest daughter Kindra or tries to impart positive affirmations on black youth in addition to Mae Mobley.Minny winds up being even more of a stereotype, an uncouth loud mouth who verbally berates members of her own community, as they attempt to join in with civil rights activities going on in Jackson, Mississippin (items in bold are my doing):

“I told Shirley Boon her ass won’t fit on no stool at Woolworth’s anyway.” (Minny, Pg 217)

And I know there are plenty of other “colored” things I could do besides telling my stories or going to Shirley Boon’s meetings-the mass meetings in town, the marches in Birmingham, the voting rallies upstate. But truth is, I don’t care that much about voting. I don’t care about eating at a counter with white people. What I care about is, if in ten years, a white lady will call my girls dirty and accuse them of stealing silver. Minny (Pg 218)

And why does Stockett have Minny making such stupid statements? Because for whatever reason, Minny apparently can’t hold her tongue when dealing with a character named Shirley Boon. But there’s also another reason. Stockett sets up the maids stories to appear as great or of greater importance than the civil unrest that actually went on in Jackson. Thus Minny distances herself from the community meetings in order to keep her appointments with Skeeter. But there was no need to disparage the very real civil rights activities to do so.

By confining Aibileen and Minny to their respective ”kitchens” and also a singular church, Stockett’s 1960s Jackson is almost idyllic in its lack of racial problems. Hence the only character in danger is Skeeter, since she has to worry about being stopped going to or from Aibileen’s house. However even then there’s no real danger, it’s only implied and never materializes.

This turns the character into a buffoon. And Aibileen and Minny become a female version of Amos ‘n Andy, where Aibileen plays straight man to Minny’s comedic lines. Which then leaves Skeeter as the dreaded “white savior” or basically the only member of this crew thinking straight. Unfortunately, when Kathryn Stockett tried to find a way to insert a white character into the mix of her maids, here’s what she wound up doing:

Note this line in the review posted below. “The colored folks actually saved themselves. Minny and Aibileen, as well as the other colored folks in the community were the real “heroes” of the movie; they just needed someone to push them to their potential (Skeeter)”

Like the novel, the notion that “someone had to push them to their potential” falls back on the stereotype that blacks could do nothing for themselves unless someone white was at the helm.

And it’s also a cringe-worthy reminder when we sought equality. The excuse most often heard was that blacks would gain equality once we “earned” it.

The line “they just needed someone to push them to their potential (Skeeter)” perfectly sums up a major bone of contention about the novel, and may also be what’s controversial about the film. Why? Because far too many people would rather believe a film than real history. Real history shows African Americans (including maids) were tired of being mistreated and maligned, so the fight and burning desire for civil rights grew out of violent and demeaning oppression. It was started by African Americans, for African Americans. It began, not in the 1960s, but when the first African American was bound and shackled centuries ago. The non-violent protests and marches during the height of the civil rights era were called the “FREEDOM MOVEMENT” for a reason.

African Americans wanted to be free, and in 1964 a law was passed to ensure we got it.

And the resulting legislation affected other minority groups, like white women and later amended to add the physically challenged.

To be continued . . .

waloof

October 2, 2011

first I have to apologize for my English, I’m French. sorry for any mistakes I’m gonna make.

sure enough this book is not as objective as it could be. this is a “white” point of view and the situation at that time was certainly worse than it is described.

though it’s interesting to learn about facts and mentalities, and personaly I’ve been encouraged to look for further information about the period. and I think that really that’s all you can ask from a novel. the Help is not a history book, but I don’t think either it’s a fairy tale.

acriticalreviewofthehelp

October 2, 2011

Hi waloof,

Thanks for your post, but respectfully, while The Help didn’t have to be a history book, it at least could have had more respect for the black culture.

It’s important to note that the movie has attempted to address and “fix” what Stockett got wrong in the novel.

Being French, I doubt if someone wrote a novel, and you found it easy to pinpoint a number of falsehoods as well as favoritism to say, the other nationalities in the book, that you wouldn’t at least speak on it.

Essentially, that’s what I’m doing.

As far as the Help not being a history book, I’m glad you mentioned that, as I think I need a post addressing this often stated excuse which gives Stockett and her publisher yet another pass.

cinnamonb

October 2, 2011

Hi –

I’ve continued to read through more of your posts.

Don’t know if you or anyone has thought of this – or maybe I’m just stating the obvious – I think that a lot of this was Stockett writing about herself; I think Skeeter must be her alter-ego. Maybe that would explain why you say this really is Skeeter’s story.

Just slogging through those quotes is a cringe-worthy experience.

Take care.

Sam Draves

December 15, 2011

This book is a work of fiction. The author has stated this many times and she has also said that she based characters off of people in her life. Give her a break! I don’t think she intended the book to cause drama. Its a good book and I rather enjoyed reading it. And I’m not racist and I don’t think Stockett is racist either. I don’t think her purpose was to insult anyone. So again give her a break! great book and I loved it.

acriticalreviewofthehelp

December 15, 2011

Hello Sam,

Most readers know this is a work of fiction. However Stockett grew up in a household that (read carefully now) practiced segregation. Which meant Demetrie, the maid Stockett says inspired this novel worked under rules that treated her like a second class citizen. Stockett admits at the end of her book that she was not allowed to sit at the same dinner table with Demetrie, simply because her grandparents still believed that, and I quote “white people didn’t sit at the same table while a colored person was eating.” Pg 448 under the section Too Little, Too Late

While you loved rousing lines like Aibileen’s Uncle Tomish words of wisdom “I told him don’t drink coffee or he gone turn colored and he twenty-one years old. It’s always nice to seeing the kids grown up fine” (Pg 91) and possibly Aibileen comparing her skin color to a roach “He black, blacker than me.” As well as Aibileen grinning, cringing (but not tap dancing darn it! That’s the one thing Stockett left out). They did nothing but leave me cold. So I’m afraid we’ll just have to agree to disagree on the merits of this book.

I found Stockett’s “vision” of Mammydom neither inspiring or funny, like many of her scenes and dialogue which miss the mark. It’s bullshit on the highest order and serve only to perpetuate the Mammy myth in 2011.

Or as Stockett was actually quoted as saying “I just made this shit up!” So who am I to argue? I wholeheartedly agree that the novel is crap.

If you loved the novel so, I’m pretty sure you loved Stockett painting most of the black males as either lazy, “no-ccount” or drunks. I didn’t.

And the whole Aibileen swears off all men after one failed marriage really was a stretch, while it endeared her to many who probably did think black women couldn’t possibly find another man attractive after the Cocoa, Cootchie, Clyde deal (Pg 23-24) The “spoilt cootchie AKA Cocoa gets a venereal disease” falls directly in line with the slurs many bigoted whites used to block integration, using the excuse that even black children carried venereal disease.

However I don’t blame you for loving this novel. Most of the males who aren’t African American make out rather well in the book and in the movie. Stockett made sure of that because she sure didn’t want to insult you and risk losing your “love.”

Thanks for your post. You covered just about every excuse why so many adore this novel, without giving any substantive facts to back it up.

Sam Draves

December 16, 2011

Again as I said before GIVE HER A BREAK! I’m not saying this book is work of genius, I’m just saying it’s good. Its supposed to be fiction not an exact reenactment of history. I’m sorry I don’t have time to go through the entire book and find examples for you! But concerning how black men are portrayed, I do believe there was a young black man that went around helping everyone and was kind to Aibileen. So maybe you should go through the book one more time….

acriticalreviewofthehelp

December 16, 2011

Hello Sam,

So this is how you defend your position? This is how you attempt to prove what I’ve written is incorrect? All you can come up with is “Give her a break” and “I don’t have time to to go through the entire book and find examples” Yet you direct me, as if you think I’m either Minny, Aibileen or Mammy from Gone with the Wind to do your work for you?

WTF?

Way to show just how much you DON’T KNOW about where Stockett went astray in her depiction of a culture that’s been mocked, maligned and mis-understood for YEARS.

And The Help is just one more degrading example.

But I’m so glad you commented TWICE. Your willingness to remain naive or ignorant, take your pick, on the numerous issues within the novel is what Stockett and her publisher, and those behind the movie were counting on. Congrats for proving them right.

Sam Draves

December 16, 2011

Dear What-Ever-Your-Name-Is,

Thank you for calling me ignorant, that really makes me consider that your points could be valid. I stated that the book was fiction and somehow you think that I think what she wrote is the truth. I do not under any circumstance believe that this story is true. I know that this is not exactly how things happened.

Just because Stockett’s family had a black maid and her family lived with segregation, doesn’t mean that she personally was racist. Just like the character Skeeter…

And I had a lot of respect for all of the maids in the book and I did not think badly of the black men in the book either. I personally disliked all of the white characters way more than all of the black characters. Just because she had one or two “drunk or lazy” black men doesn’t make me think bad of all black men. There are millions of drunk and lazy people around the world and many of them are white. So maybe you should again just accept the book as fiction and stop going through and finding every single inaccuracy in this book.

I hope this was a good explanation for you.

acriticalreviewofthehelp

December 16, 2011

Hello Sam,

I’m afraid we’ll just have to agree to disagree on this book.

I encourage you to read other posts on this blog. Perhaps it may be helpful for you to google “segregation” so you can get a better understanding regarding the problems with Stockett’s depiction of her black characters, from actual testimonies of individuals who experienced the time period and who were domestics.

The saintly, devoted maid, or Mammy is not an honorable character to many African Americans. It’s a stereotype. Aibileen, Minny as well as Constantine unfortunately default into this caricature in Stockett’s novel.

Much of what she wrote was offensive, and inaccurate. Not just to me, but to scholars and professors like Melissa Harris Perry, Martha Southgate, among others who’ve spoken out against the book.

You may be surprised to know that even Stockett admits she got parts of the novel wrong.

Amber Maiden

January 19, 2012

Wow…you certainly do have A LOT to say about this book! And much of it is very true. It’s very difficult for any writer to realistically write about any other’s race or culture with any real meaning or depth, because you’re always on the outside looking in. Yes, it’s true that in “The Help” you do have a lot of stereo-typical, dumbed-down, this is very clearly a white-washed, white perspective of a particular time and place.

But being that the writer was white, writing from her particular place and time, I think that she honestly did the very best she could do to tell an interesting underdog story from her limited perspective. I mean what did you expect? She ain’t Angela Davis and probably doesn’t even know who Angela Davis is.

So what are you really expecting from this white girl? You should expect exactly what you got, flat, two dimensional black characters and the great big white hope of a white girl coming to the rescue. Are you really surprised or offended by that?

Maybe offended, a little, I’ll give you that. But surprised? Come on! That is the typical Hollywood formula for these types of stories. Usually though, it’s some white man who is the great white hope to the world. Honestly, it was nice to get a slightly different take on the same old Hollywood story. I will agree that white writers who are seemingly unable to tell a biracial or bicultural story any other kind of way are ridiculously unimaginative. Or maybe not. Maybe they just want to sell, because the truth is, the white masses really don’t want to hear this kind of story any other kind of way.

I didn’t read the book, I probably won’t, but I did see the film and I enjoyed it. I know that you will hate what I’m about to say about it, but I actually I found it provided a great deal of insight into the reasons why so many black people from the South, were AND STILL CONTINUE TO BE, so step-and fetch-it-ish.

And I say this from personal experience. I say this from wanted to SCREAM, at so many of my Southern brothers and sisters, “Slavery over, yall! STOP IT!”

A lot of them, seriously, did not get the memo. They need to read up on Angela…cause “Skeeter” ain’t the only one who doesn’t know her name. And I’m guessing from the tone of your nearly novel of a post, that’s a reality you just don’t want to face.

But it’s true.

Every black person in America ain’t brilliant. A lot of them, and certainly many of the southerners on both sides of the color line are stuck in step-it and fetch it mode, for reasons far too complicated to delve into here. Lots of them, really do say and do stupid shit, marry abusive men, and act inelegantly on the bus, or in other private or public places. (Hell, I’ve acted inelegantly on the bus and in other private and public places.) You can’t hold that against the white writer who watches, listens, takes notes, writes it down in a book, and becomes a bestseller.

I mean you can- because obviously you have- but it’s a waste of time and energy. Just take the book for what it is, white-washed, dumbed-down, slightly, ever so slightly, historically based, dopily feel-goodish story about some maids rising up with the help of the great hope white girl Skeeter. (Who actually does come off as shallow, self-interested and opportunistic to me, but not nearly as shallow, self-interested and opportunistic as the rest of her crew, which actually does make her more real, human and redeeming.)

acriticalreviewofthehelp

January 20, 2012

Hi Amber,

Thanks for your post.

“But being that the writer was white, writing from her particular place and time, I think that she honestly did the very best she could do to tell an interesting underdog story from her limited perspective. I mean what did you expect? She ain’t Angela Davis and probably doesn’t even know who Angela Davis is.”

I disagree. Doing the very best she could would entail at least doing a google search on how Medgar Evers was murdered. When the author couldn’t recall in three audio interviews what she wrote in her own novel, that calls into question just how much research she actually did. And since the book was touted using civil rights as a backdrop and also inserting actual events into the storyline, it’s important to note that Medgar Evers was not fictional. He was a father, a husband and a civil rights icon who was assassinated by a bigoted member of the White Citizen’s Council of Jackson, MS.

I also don’t think writing a novel and then being questioned on it deserves a “I just made this shit up!” response by an author who white washes not just history, but how the black and white culture responded to segregation.

Stockett’s “we love them and they love us” premise was simply a resurrection of the antebellum myth begat in slavery, that the slave so loved his/her master.

Stockett has also become a very wealthy woman simply because a group of southern friends got together to write a book and a novel on how much fun they had with their black maids. Yet she ignores the real life maid Abilene Cooper, who still works for her brother, which underscores just how much compassion she truly has for domestics like her childhood maid, Mrs. Demetrie McLorn.

You may want to read the posts I’ve listed below for a better grasp of what The Help is really about, both the book and movie:

Whether or not Kathryn Stockett knows who Angela Davis is has no bearing in a discussion of the novel or movie. But to let her slide simply because she “did the best she could” is pandering to the thought that because she’s white she couldn’t have researched the web or consulted with educators, resources which are available freely to all, regardless of race. Minorities are required to know American history, which is told from the point of the predominant racial group in this country, which is white. Unless the school districts around the country make an effort to be inclusive, then other cultures are not included in primary education, contrary to what some news agencies like to report.

Thus many sections of the country, as per a current study by the Southern Poverty Law Center reveals that many states have failed to adequately teach the Civil Rights Movement:

http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/news/splc-study-finds-that-more-than-half-of-states-fail-at-teaching-the-civil-rights-m

“So what are you really expecting from this white girl? You should expect exactly what you got, flat, two dimensional black characters and the great big white hope of a white girl coming to the rescue. Are you really surprised or offended by that?”

Kathryn Stockett is not a girl. She was in her late thirties when the novel was published. That’s more than enough time to realize not to demean and mis-represent one culture while white washing another.

And because I experienced segregation, of course I’m offended. The question is, WHY AREN’T YOU?

“I didn’t read the book, I probably won’t, but I did see the film and I enjoyed it. I know that you will hate what I’m about to say about it, but I actually I found it provided a great deal of insight into the reasons why so many black people from the South, were AND STILL CONTINUE TO BE, so step-and fetch-it-ish.”

You may want to think about that. If you saw the movie and have no idea how African Americans were portrayed by Old Hollywood and in American society during the dark days of segregation, then I say this in all due respect and sincerity. Educate yourself.

“Frying chicken make you tend to feel better about life” stated by Minny in the film is offensive no matter how you cut it.

African Americans were linked to chicken mockingly during slavery, during segregation and even now.

“You is smart, you is kind, you is important” is something Minny’s kids could have also used as daily affirmations, not just Mae Mobley. But the antebellum myth of black mammies instilling love and strength into their white charges while demeaning their own community is more prevalent in the novel. Still the movie doesn’t show Aibileen coddling or instilling positive affirmations into any black child during the film.

“Every black person in America ain’t brilliant”

That goes for any racial group.

“And I say this from personal experience. I say this from wanted to SCREAM, at so many of my Southern brothers and sisters, “Slavery over, yall! STOP IT!”

A lot of them, seriously, did not get the memo. . .”

Okay, I read your whole post. Now you’re just running off at the mouth, not running it.

Invoking Angela Davis’ name without context or even applicable quotes to bolster your comments just doesn’t cut it here. Do better.

And keep in mind, I was around back then in real time should you wish to return and drop some knowledge. But I digress. Returning to The Help

The resurrection of the stalwart, obedient black Mammy is as American as apple pie and you just admitted it was cool with you. There were two types, the shy, quiet one, which Viola Davis plays. Louise Beavers perfected this role back in the 30s. Octavia Spencer is an updated Mammy from Gone with the Wind. That’s why she’s so “sassy” yet she just admitted in a recent interview she doesn’t want to do any more roles where she plays the “sassy” black woman. I’m afraid she may be typecast after The Help.

And the legendary actress Cicely Tyson, who I chose to recall from better days is an Ethel Waters hybrid of the two.

Back to Minny and her “sassiness”:

Had she really fed any white woman a shit pie and boasted about it, she wouldn’t have lived to see another day. While “Eat my shit” may play well with modern audiences, its as bad as inserting Arnold S into the movie to state “Hasta La Vista bigots” complete with Terminator gear and sunglasses.

So you see, there’s fiction and there’s fantasy. What you saw and enjoyed was fantasy.

“I mean you can- because obviously you have- but it’s a waste of time and energy”

Yet you took the time to write a long drawn out . . . I’m not sure what this is.

But I do know this. Next time I hope you’ll bring more facts and less frustration.

Heather Ryan

March 23, 2012

Gosh, I’m only on Chapter 11 and I’m debating whether or not I should devote my full attention to finishing “Letters From Alcatraz,” (which is amazing, AND factual, by the way.)

Seriously, nothing bothers me more than factual information stated (and/or portrayed) incorrectly due due to lack of research. Who wants to look ignorant when it so easily could have been avoided?

I applaud you and this amazing blog!!

Kagi (@soracia)

August 29, 2012

Wow people are giving you a lot of static on this post…most of the others don’t have any comments, and most of the comments elsewhere are positive. That I’ve seen, I haven’t read the entire blog, but a good half of it I guess. I’ve been kind of glad that there hasn’t been more negative comments, but I guess a lot of them were hanging out in this post. Why this one, I wonder.

Anyway, thank you so much for doing this, I’ve always had a very bad feeling about the book/movie since I heard about it, and never wanted to watch or read it, but everyone always spoke so highly of it that I wondered if maybe it was just me. I’m glad to have a detailed look at the problematic things so I know what to tell people other than I just didn’t like the sound of it!

acriticalreviewofthehelp

August 29, 2012

Hi Kagi,

Thanks for your comment. I tend to delete the ones who veer off the subject of the post. But I think I’ve read two quotes which aptly sum up why many people love Stockett and Tate Taylor’s (director and screenwriter of The Help and possibly ghost co-author of the novel) creation called The Help

Skeeter was needed “to push the maids to their full potential” and they weren’t just “any regular Mammy.”

Jean Ochenkoski Gagnon

September 4, 2012

I found your blogs very thought provoking, which is reason enough to have them. I, too, found the site after trying to do more research into “Carl Roberts”. My 15 year old daughter and I just finished reading the book together and will be watching the movie soon. I thank you for all the work you’ve done regarding this. At the time I found the book very enjoyable, but now I’m questioning why I enjoyed it. Was it because as a white woman it made be feel good, at the expense of those that really suffered? Why, as an intelligent person, didn’t I question the stereotypes presented? You’ve given me much food for thought, and some good starting points for a real conversation with my daugher regarding the book, the movie and the civil rights movement. Thank you again.

ekanthomason

December 24, 2012

Are you Miss Hilly? or one of the other characters in the book? How do you happen to have a photo of her maid?

acriticalreviewofthehelp

December 24, 2012

Hello ekanthomason,

Nope, I’ve got no connection to the author at all. I just used an internet search engine.

Rachel Glenn

March 4, 2013

Hello, i must agree with you on all of the examples you have listed. But there is just one thing i must point out. This book, is in fact iction. It even says it on the back of the book at the bottom by the bar. A fiction novel is not ment to have exact historical examples. It is just supposed to have enough correct information to be able to tell the time period.

Here is a definition of fiction:

fabrication applies particularly to a false but carefully invented statement or series of statements, in which some truth is sometimes interwoven, the whole usually intended to deceive.

fable, fantasy. fiction, fabrication, figment suggest a story that is without basis in reality. fiction suggests a story invented and fashioned either to entertain or to deceive: clever fiction; pure fiction.

I do see your point on wanting to have it to be more of a historical fiction, but i did enjoy the book all together even if many of the characters were not real.

acriticalreviewofthehelp

March 4, 2013

Hello Rachel,

Thanks for your comment. I’m not sure you understand the point of the post. It’s titled “Fact vs. Fiction” because I received so many questions on items in the book, so I wrote a post covering them. I know the book is fiction.

The items listed cover questions from readers, which were sent to me, or either the top searches from sites like Google and Bing, which then direct the individual to this site. Questions/searches such as, was there a Carl Roberts who was really lynched? However, if you’re referring to items #9 and #10, please note I list the question or statement in Italics first and then I answer it, and so I’m not going to reiterate it in this reply.

I hope that clears up any confusion.

Bigdaddyo Optional

May 12, 2013

Well isn’t it just like a white person to lie when confronted with the truth, she knows the book is based on true events like her grandmothers maid. Why do you think the native Americans said the white man speaks with forked tongue.

Anne Trophy

May 26, 2013

Wow. Am I ever glad I was born and raised in the Caribbean. Even if the book portrays events badly, it is horrid to be ‘free’, yet not really so. Saw the movie last night and it confirmed my gratitude for where I come from and that colour has never been an issue in my life or even my grandparent’s lives. Cicely Tyson is from my island. She did a great job as always. Thanks for the above assessment of the book. Was thinking of buying a copy, but that’s now out the door. Racism is an awful disease and I’m very happy my parents and I never endured it (I’m 53 yrs old). All the best and personally I believe that only the Bible should be taken seriously. Regards.

Holli Vaine

August 12, 2013

This post reminds me of an Extra Credit’s episode (a show on youtube devoted to discussing video games) where they talk about Call of Juarez: The Cartel. That game deals with the Mexican Drug war but it handles the topic so badly and it’s so poorly researched that it becomes a detriment to it’s audience because it misinforms them. The game is also very racist, but that’s neither here nor there. The Help is like that too: it gives uninformed people a very skewed and inaccurate picture of the time and the setting. And it’s also racist. I hadn’t realized quite *how* racist until I started reading reviews and blogs like this one. When I first read the book, I disliked it because of its protagonist–now I have brand new reasons to dislike it.

Anyway, the point of the anecdote is to thank you for taking the time in this blog to set the record straight, as it were.

Anne Bishop Sterrett

December 26, 2013

Hello there, Critical Review!

First I’d like to thank you for writing. It takes courage to shine a light on truth, especially when the truth goes against what is popular (particularly for emotional reasons) with others. I too lived in the South during desegregation. I wonder your age at the time. I hear your concerns of more misinformation and negative stereotyping towards African Americans, and I understand as best I can, not being from that group. I think the challenge comes in accepting another’s perspective. I see the book as a work of fiction designed to impart the perspective of how an adult child of the post-desgregation era comes to terms with the relationships between white children and their African American Caregivers, “Maids” or “Help” as they were known.

I was an elementary school child during the most tumultuous years in Jackson Mississippi. This puts me several years older than Katheryn. Having a younger brother her age, I am amazed at the different ways in which we have experienced the same events. I wonder if the some of the differences between your views and hers are due to age difference. I am sure those of different racial backgrounds experienced this period differently (to that, I am sure you are saying “duh”). In my memory of those times, unbiased information was difficult to find. It was certainly not presented often for public consumption, as you have pointed out. In addition, the fact that so many generational southerners who held the keys to social status considered themselves set apart from the United States, created a disconnect which disallowed any sharing of perspectives (in polite social settings) that I can remember. I lived it, too, and this is MY perspective, no doubt full of flaws and fiction, but it is a true perspective.

I appreciated Katheryn’s perspective on the relationships between white children and their African American care takers. There was an odd and difficult to define love relationship which was full of paradoxes. I believe in the humanity of others and good present in all of us. I believe in the desire to love and to build intimacy with those who hold places in our lives, regardless of the reasons they hold those places. I believe that love did exist between white families, especially children and the African American domestic workers even though the relationships were based on awful truths and inequality.

I also know that cruelties did exist. I know that they still exist today. Although I have not lived in the south for many decades, I pray for those who do. I continue to grow past the places and perspectives of my childhood including the many falsehoods I heard about people of color. I hope that I am able to make a positive difference in this world. AND I am glad to read about love that existed during those complicated times.

Thank you again for your perspective.

Hannah Brown

January 5, 2014

You’re right. Everything you said is right. There’s probably even more wrong about this book than you’ve uncovered (and I know you have like 4+ blogs on this very topic). But it happened. I’m not talking about the stuff in the book. What I’m talking about is the fact that it was written, it was published, it became popular, it became a bestseller, it had a movie adaption, etc. So you know… there’s nothing you can do to change that now. Even if they fix all the errors, there will still be millions of copies out there that are still factually incorrect. And you know firsthand how ignorantly defensive people get when it comes to criticizing this book, so there’s no point in trying to convince them of the errors. So we all just have to forgive and forget, you know? I admire the amount of research that you put into your blogs about this, though. I’m just saying… okay this is gonna sound crazy… but hear me out. I have a better idea. You’ve proven yourself to be a really good writer and you clearly have enough common sense to Google facts before you write something down (you stated several times that the whole bludgeoning vs. shooting thing could have just been Googled). So I think you should rewrite your own version of the book. Sounds crazy, I know. I just feel that I would be interested to read your version of the story since you are obviously of a much higher intelligence than Kathryn Stockett. And think of all the things you can change! Skeeter won’t have to be the white savior. Minny won’t have to get away with being “sassy.” It’ll be so accurate because you know exactly what happened back then. I mean, if you don’t have time to do something like this I totally understand. After all, it did take Stockett five years to write this book. It’s just an idea of mine. It may be a bad idea. It may be a good idea. I have no clue. I just wanted to put it out there. Anyways, after that long explanation of my idea, all I have to say is this: I liked it. The book. I know now that it’s pretty factually incorrect and offensive now that I’ve read your blog, but I liked it when I read it the first time. My favorite parts were when Minny saved Celia from dying when she had a miscarriage, and when Celia saved Minny from the naked guy who was in Celia’s yard. Did you like any parts in the book? I know there’s a lot of parts you didn’t like, but were there any you did like? Thanks for reading my comment.

Yeah I realize it’s been six months since somebody has commented on this blog but whatever.

acriticalreviewofthehelp

January 16, 2014

Hello Hannah,

Thanks for your post.

Comments are moderated, and I usually update them when I can get to this blog. So in answer to your observation about no one posting here for six months, there are comments and questions waiting in moderation. However, a few instructors have assigned the book and a number of students seem to think this site is a homework hotline on The Help, when it’s not.

So I usually choose the comments that end up getting post on here. The truly ugly ones I delete.

As far as you enjoying the novel, please understand that it was written just for that purpose, and judging by the multitude of others enamored with the book, I’d say it did what it was intended to do. I’m not part of the publisher’s coveted “target audience”. The novel wasn’t meant for someone like me, who recalls segregation and doesn’t feel all warm and fuzzy about, quite simply, Skeeter’s coming of age tale using the stereotype of the sassy black maid and the saintly, obedient, black maid AKA Mammy from Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell (Minny’s feisty character) and Delilah from Imitation of Life by Fannie Hurst (the character of Aibileen). Constantine was a rip off of the parts Ethel Waters usually played on stage and screen, that of the comforting, advice giving black domestic. The book expertly emotionally manipulated those unaware of actual history, and how “we love them and they love us” is an antebellum myth that was started, ironically, by slave owners and passed down from generation to generation.

Should you be inclined to read any additional posts on this site, please take a look at how The Help came to be, and how Kathryn Stockett, Tate Taylor and even Octavia Spencer planned their work and worked their plan, because each one wanted, and got something out of an early “agreement” the three had:

Also, I’ll leave you with these quotes from historian Micki McElya, author of the book Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007

“If we are to reckon honestly with the history and continued legacies of slavery in the United States, we must confront the terrible depths of desire for the black mammy and the way it still drags at struggles for real democracy and social justice.”

“so many white Americans have wished to live in a world in which African Americans are not angry over past and present injustices, a world in which white people were and are not complicit, in which the injustices themselves — of slavery, Jim Crow, and ongoing structural racism — seem not to exist at all.”

For more on the antebellum ideologies on race that have been transplanted to modern times, please see this post: https://acriticalreviewofthehelp.wordpress.com/2010/10/21/the-affection-myth/

Donumdeae Poculum

February 15, 2018

I watched the movie when it was released in Germany and read the book afterwards. I have to admit that I liked it, because it is created to be liked by white privileged women and girls. In fact, as a high school student books and movies like “The Help” or “The secret life of bees” were my only sources for getting an idea on how segregation in America was like, because East-German history teachers seem to have plenty other issues to talk about. Therefore, I am very grateful for your blog showing Stocketts lack of research. As a reader, I somehow expect it to be done far better, especially as there are authors and publishers even of historically-based fiction who did so. I also wonder how she could have missed this, having studied Creative Writing and worked in publishing.